Private equity in gaming: Could more deals be coming?

Since the start of the year, US gaming has seen three high-profile deals facilitated by private equity.

The most recent was 26 July, when Apollo Global Management announced it was acquiring suppliers IGT and Everi Holdings in a $6.3bn deal. The deal is structured so that IGT’s gaming and digital divisions will merge with Everi’s gaming and fintech (financial technology) families to create new a private entity under Apollo. IGT’s lottery component will re-list as a separate public company.

IGT and Everi had already agreed to merge in February, but that deal was superseded by the private equity giant. Between games and fintech, both companies hold a commanding presence on just about all US casino floors. In Q2, IGT posted just over $1bn in revenue and Everi posted $191m.

Bally’s becomes only operator owned by private equity

One day prior to the Apollo deal, hedge fund Standard General (SG) completed its quest to buy out Bally’s Corporation. SG, which is headed by Bally’s chairman Soo Kim, paid $18.25 per share. This was a significant discount from its previous offer of $38 per share in 2022, which Bally’s rejected. Since that time, the operator has been plagued by stock declines and mounting debt, making a buyout more appealing.

The transaction is expected to close in the first half of next year.

As part of the deal, Bally’s will merge with Queen Casino & Entertainment, a regional operator also owned by SG. The combined company’s portfolio now includes 19 casinos in 11 states. It will remain a publicly listed entity in SG’s portfolio.

Bally’s will become the only major US operator owned by private equity. All others – including Wynn Resorts, MGM Resorts, Caesars Entertainment, Penn Entertainment, Red Rock Resorts and Boyd Gaming – are publicly or family-owned.

Brightstar bets big on AGS

Before Apollo swooped in on IGT and Everi, Brightstar Capital Partners made its own splash by acquiring supplier AGS for $1.1bn in May. Brightstar paid $12.50 per share, a 40% premium over its price on 8 May, the day before the deal became public. The deal was approved by shareholders on 6 August.

AGS had been publicly traded since January 2018. Prior to that it was also owned by Apollo. The company is seen as an up-and-comer in the games space, with an iconoclastic style. Its table-game and interactive divisions have also seen substantial growth in recent years.

In 2021, the company’s Bonus Spin Xtreme table-game solution won the gold medal for Best Table Game Product in GGB’s Gaming & Technology Awards. In 2023, its Triple Coin Treasures game on the Spectra UR43 cabinet won silver for Best Slot Product.

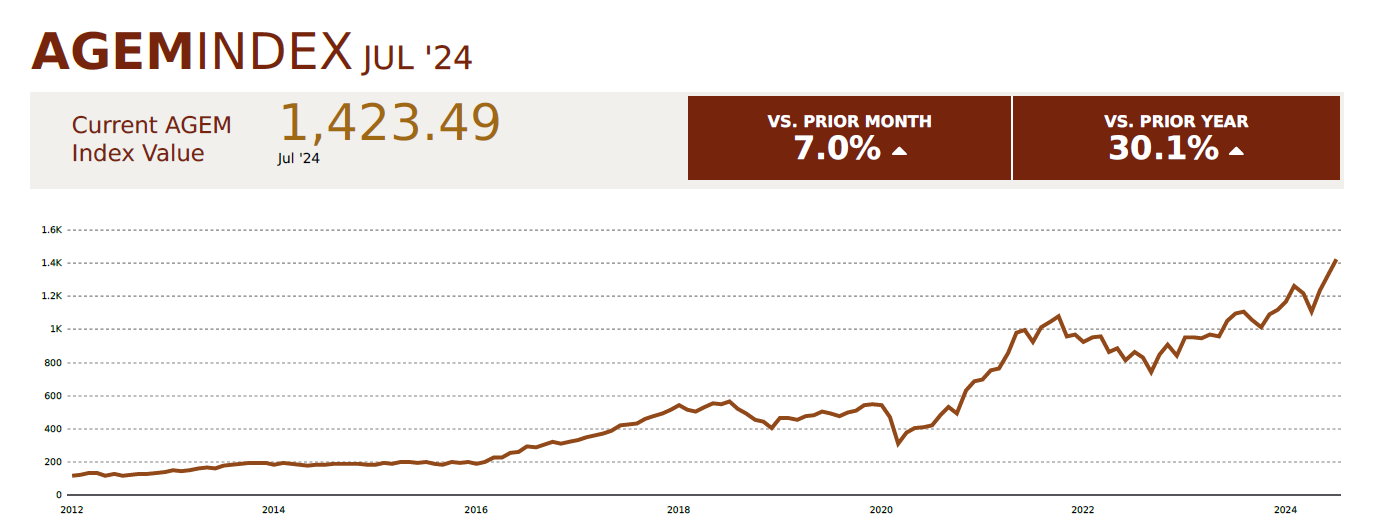

Overall, suppliers appear to be gaining momentum. In July, the Association of Gaming Equipment Manufacturers (AGEM) Index, a stock index featuring 12 suppliers including IGT, Everi and AGS, increased 7% from June and 30% from last July.

Are investors optimistic or opportunistic?

Frank Fantini, founder of Fantini Research (and longtime columnist), told iGB that the recent trend is reflective of low valuations rather than an increased interest in gaming. The majority of popular gaming stocks are well off their all-time highs, many of which were reached in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. As such, the companies have become increasingly attractive to groups looking to make a profit.

“Private equity groups haven’t changed their motivation or mode of operation,” he said. “They still buy assets in order to sell them later at a profit. Apollo doesn’t want to become the biggest casino operator. I think it’s more taking advantage of the depressed valuations because they can do it as private investors.”

As a career gaming investor, Fantini said the recent wave of deals is just the latest chapter in the financial history of the industry. Until the late 1970s and early 1980s, gaming was mostly a private business.

But the growth of the Las Vegas Strip and Atlantic City’s decision to start opening casinos in 1978 allowed operators to go public to fund their growth plans. This second phase was buoyed, Fantini said, by pioneering figures like Steve Wynn and Sheldon Adelson who attracted a level of investment the industry hadn’t yet seen. After multiple decades of non-stop growth, the market is more mature and thus harder to succeed in.

“Now you have kind of a third wave where you have a little bit of retrenchment from that because those visionaries are gone now,” Fantini posited. “And corporate ownership isn’t faring as well.”

Who’s got the cash?

One dynamic that is currently working in private equity’s favour is freedom of movement. According to Rick Arpin, US gaming leader for professional services firm KPMG, fellow gamers are having a hard time positioning themselves to broker deals.

“The problem is, other [gaming] companies can’t take advantage of [low valuations] like private equity can,” Arpin said. “They don’t have the capital resources. They’d have to go borrow and borrowing’s expensive. Their equity’s not trading well either. So it’s opened up the field for private equity to be one of the primary sources of acquirers in the space.”

Gaming has relatively high barriers to entry, mostly in licensing and other regulatory requirements. So, once a group does buy a gaming asset it becomes easier to acquire more if they wish to. They can also exit and re-enter the industry with more knowledge and experience, as Apollo has done.

“It’s not a surprising trend,” Arpin asserted. “It makes sense from what’s happening in the valuation space in our industry…. I wouldn’t be surprised if we see some more.”

What about the bookmakers?

With supplier and operator deals in tow, that begs the question of whether a top sportsbook could be taken private. Most of the major US bookmakers are public or tied to public companies. This includes FanDuel (Flutter), DraftKings, BetMGM (MGM-Entain), Caesars Sportsbook and ESPN Bet (Penn-Disney).

The only exception is Fanatics Sportsbook, which is majority owned by Fanatics CEO Michael Rubin. SoftBank Group and Silver Lake Partners are also investors in the business. IPO rumours have circled the company for several months, which have been denied. But a company source told Front Office Sports that an IPO is the “most likely long-term outcome”.

Chris Grove, sports betting investor and partner emeritus at Eilers & Krejcik Gaming, does not think any private deals are coming soon. Out of all gaming verticals, sports betting is perhaps the hardest to break into. Revenues are climbing, but margins are thin and customer acquisition costs are higher than ever.

“We’re unlikely to see any of the top five digital operators in the US taken private in the near term,” Grove told iGB. “There’s too much complexity, too little demand and the value proposition is a bit unclear.”

Part of the problem is that most bookmakers have spent heavily for years to grow market share. That steep level of investment makes future profitability even more attractive, especially for the top players.

“DraftKings, FanDuel and, to a lesser extent, Caesars and MGM are all on a clear path to profitability,” Grove said. “It’s just not a market where anyone who opens a sportsbook is guaranteed to succeed. But the underlying market is incredibly attractive and will eventually generate billions in annual profits.”